Object Oriented Programming

Object Oriented Programming!

I am trying to contribute to open source recently and it’s hard, but apart from that Open Source projects use a lot of object oriented programming.

In this short blog post, I will break down OOP to you in simple terms, this won’t be syntax focused but it goes a little bit deeper.

Why do we need objects in the first place?

Objects make our program more functional, useful and reproducible. Imagine you have started a new bank in a remote area of your city, and you are making an account opening form for your new bank.

Now many people would want to open an account in your new bank, as a result you need many forms but you don’t want to make them again and again and so you save them on your computer and print a lot of copies of it to give to a new account holder. OOP is quite similar to this.

Classes and Objects

In programming, classes are similar to the form stored in the computer and objects are like printed forms.

Classes are just like the digital form that we saved above, while objects are the printed forms. Printed forms are the copy of the digital form, yet digital they are not the digital forms. They have the same structure like digital form but they are not the printed forms.

In Python, it’s quite simple to define a class:

class MyClass:

x = 5

But this is just a simple class, and it does not do very much. We need to put some functions inside this class to make it more functional:

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

Now this is a very simple class with just a single function. But this function is a very special one. Generally, special functions start with two underscores (__), in Python.

_ _ init _ _ (keep two underscores together, in code!) function tells what to do when you make an instance of your class, or according to our analogy, when you print a new physical copy of that digital form.

Everything inside this _ _ init _ _ function is initialized upon making an instance of this class, i.e., all the variables and whatever you put here.

But apart from this, we can put as many functions as we like inside a class, and we can make them do whatever we want them to do.

Here is an example of a class with multiple functions:

class Person:

def __init__(self, name, age):

self.name = name

self.age = age

def myfunc(self):

print("Hello my name is " + self.name)

This is a class with multiple functions. Here is an example of what you might encounter in a real-world scenario:

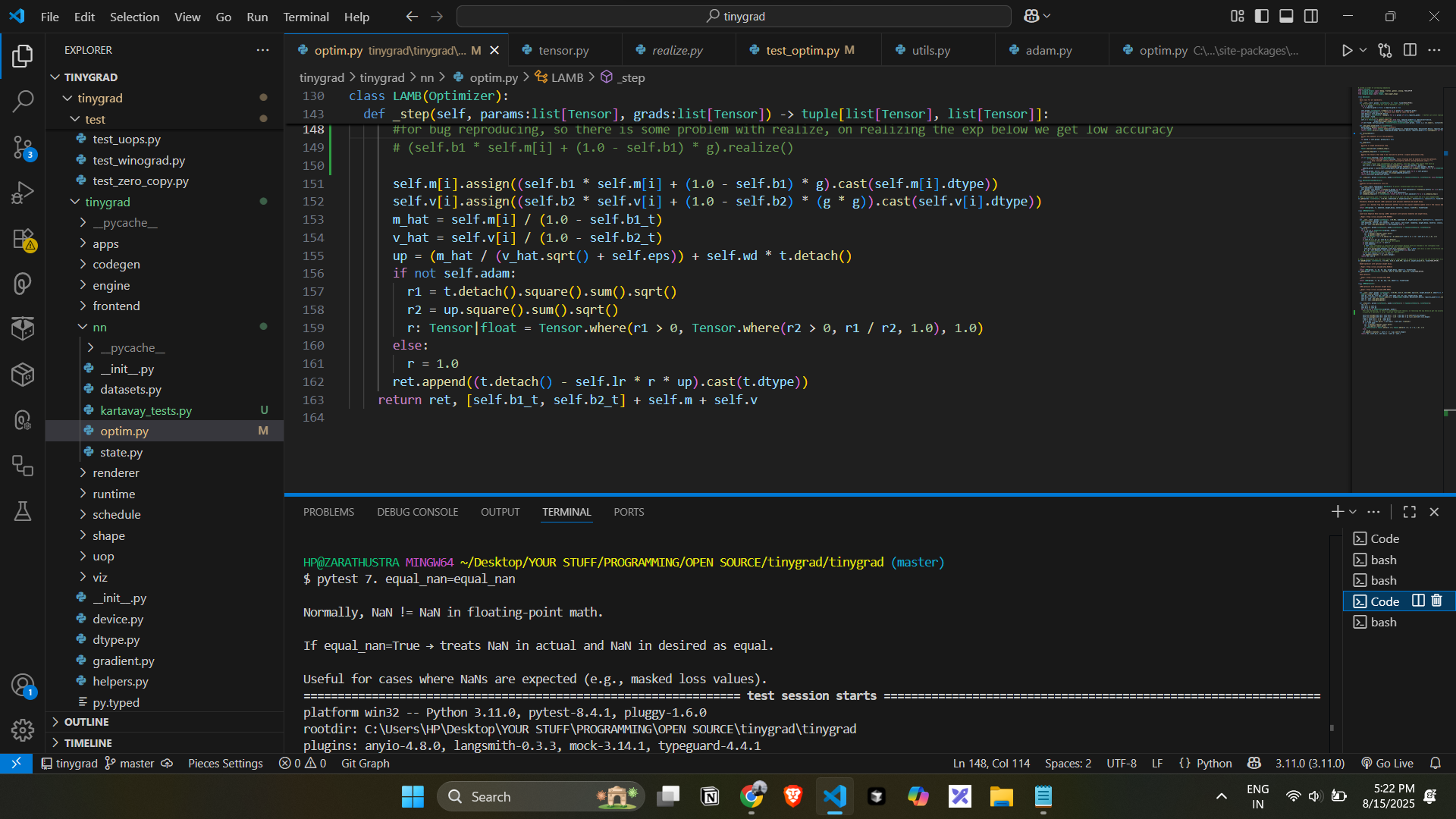

class LAMB(Optimizer):

"""

LAMB optimizer with optional weight decay.

- Described: https://paperswithcode.com/method/lamb

- Paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.00962

"""

def __init__(self, params: list[Tensor], lr=0.001, b1=0.9, b2=0.999, eps=1e-6, weight_decay=0.0, adam=False):

super().__init__(params, lr)

self.b1, self.b2, self.eps, self.wd, self.adam = b1, b2, eps, weight_decay, adam

self.b1_t, self.b2_t = (Tensor.ones((1,), dtype=dtypes.float32, device=self.device, requires_grad=False).contiguous() for _ in [b1, b2])

self.m = [Tensor.zeros(*t.shape, dtype=dtypes.float32, device=t.device, requires_grad=False).contiguous() for t in self.params]

self.v = [Tensor.zeros(*t.shape, dtype=dtypes.float32, device=t.device, requires_grad=False).contiguous() for t in self.params]

def schedule_step_with_grads(self, grads:list[Tensor]) -> list[Tensor]:

self.b1_t *= self.b1

self.b2_t *= self.b2

for i, (t, g) in enumerate(zip(self.params, grads)):

self.m[i].assign(self.b1 * self.m[i] + (1.0 - self.b1) * g)

self.v[i].assign(self.b2 * self.v[i] + (1.0 - self.b2) * (g * g))

m_hat = self.m[i] / (1.0 - self.b1_t)

v_hat = self.v[i] / (1.0 - self.b2_t)

up = (m_hat / (v_hat.sqrt() + self.eps)) + self.wd * t.detach()

if not self.adam:

r1 = t.detach().square().sum().sqrt()

r2 = up.square().sum().sqrt()

r: Tensor|float = Tensor.where(r1 > 0, Tensor.where(r2 > 0, r1 / r2, 1.0), 1.0)

else:

r = 1.0

t.assign((t.detach() - self.lr * r * up).cast(t.dtype))

return [self.b1_t, self.b2_t] + self.m + self.v

This looks dangerous but you don’t need to care about it too early.

Inheritance

Inheritance is a simple concept in OOP. It is the mechanism of attaining the properties of one class (also parent class) by another class (also child class).

class Person:

def __init__(self, fname, lname):

self.firstname = fname

self.lastname = lname

def printname(self):

print(self.firstname, self.lastname)

class Student(Person): # Student inherits properties of Person class

pass # pass allows to leave code empy that otherwise needs to be filled

The class, which is the child class of another class, inherits all the properties of that “another class” (also parent class).

There is also another special method: .super(). This gives you access to all the methods or variables of the parent class, and you can assign them whatever values you want to.

class Student(Person):

def __init__(self, fname, lname):

super().__init__(fname, lname)

Encapsulation

Encapsulation is also another simple thing in OOP. As the name might suggest to you that people who made this language are talking about some sort of capsule (kidding!).

But it’s quite similar to putting something inside a capsule and blocking it from the outside world.

When you encapsulate some method or variable of the parent class, it’s not available outside that class, not even to the child class; it’s only available to the parent class.

To encapsulate something inside a class, just use: __, before the name of that method or variable, and that becomes private and, as a result, available to the parent class only.

But it’s not actually making some variable or a function “private” in the strictest sense because we can access that variable using:

obj._MyClass__private_method()

Here is a simple example of encapsulation:

class Person:

def __init__(self):

self.__name = "Kartavay"

self.fame = 0

# __name thing is not available outside the class!

Polymorphism

This is another simple property; there is no need to get intimidated by this.

Since we know that the child class inherits all the properties and methods of the parent class, a natural question might arise whether we can have functions of the same name in both the child and parent classes, and if this can cause some conflict in naming?

The simple answer is no, Python allows us to create functions with the same name in both parent and child classes. This is called polymorphism.

An example:

class Person:

def __init__(self):

self.__name = "Kartavay"

self.fame = 0

def info(self):

print("This is the parent class")

class Student(Person):

def __init__(self):

self.__name = "Teenage Kartavay"

self.fame = 100

def info(self):

print("This is the child class") #both parent and child classes have the same method named info

There is also another thing called multiple inheritance, which is possible in Python. It just means that one object can inherit or take properties from multiple classes.

Some more properties

Suppose you want to create a method (also a function inside a class) inside the parent class, but you don’t want to make it available to its objects. You can do that by using a decorator: @staticmethod before the function name.

@staticmethod

def info():

return "I am a static method"

You might notice that we are not using “self” inside the function here. This is because we generally use “self” for the methods that we want to access outside the class. Since we don’t want to use this method outside the class, we don’t use “self”.

That’s all for this article!